Money and Inventing

by Mike Marks

Driven by visions of pots of gold, inventors spend countless hours conjuring, developing, and perfecting an idea. If an inventor is fortunate, the idea is one that can achieve commercial success and pay a return on the inventor's inspiration and sweat. Unfortunately most inventions never make it to market. Of those that are commercialized, only a few actually make enough money to repay an inventor for risks taken and time and money spent.

The single most important question an inventor must ask, at the earliest possible stage, is whether or not an invention should be developed at all. Inventors should heed the words of Thomas Edison:

"Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration."

In other words, the idea is the easy part. I would add further, that once an inventor starts perspiring, it is hard to stop. Each hour or dollar spent developing an idea can become justification to spend yet another hour, yet another dollar, until fatigue, an empty bank account, or just possibly success, ends the cycle.

The purpose of this essay is to help inventors determine, on their own, which ideas are worth pursuing and which should be discarded. Third party evaluations by reputable organizations such as Invention City's Brutally Honest Review can be quite useful too. A third party evaluation is critical if an inventor is unable or unwilling to perform a thorough self-evaluation.

Many inventors begin by asking whether an idea can be patented. This is the wrong first question. A patent is only useful if an idea can make money and then, only if the patent itself helps the idea make money. The most important question to ask, at the very beginning, is this:

"Can I make enough money from my invention to justify developing it?"

Many elements contribute to answering this question but, above all, the answer depends on customers. Will anyone buy the product? It is truly amazing how many inventors proceed without research on this fundamental point. Some inventors feel that people will buy anything put it in front of them. "Look at the Pet Rock," they say.

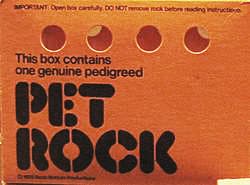

Yes, let's look at the Pet Rock. For those who do not know, the Pet Rock is a... rock! It's packaged in a cute, brightly colored, cube shaped, cardboard box that looks like a cage. Printing on the box tells the pet owner how to care for his or her rock and details the joys of Pet Rock ownership. In 1976 this was considered very funny and the product sold 1.5 million units in six months at retail prices in the $7.50 to $10 range (the item cost maybe $0.50 - $0.75 to produce). Then, as quickly as it arrived, the Pet Rock faded off the shelves and into cultural history... never to be seen again. Well, "never" is a word that should never be used in marketing. Maybe we will soon see a resurgence of the Pet Rock!

But the Pet Rock is not an example that people will buy just anything. Rather, it is an example that people will buy a particular thing at a particular point in time if it suits their fancy. Surveys of prospective Pet Rock customers in 1976 surely indicated that the market potential was huge. In 1977 surveys of prospective customers surely showed that the market was dead. What does the market think of the Pet Rock today? Go out and ask.

This brings us to the first step in determining an invention's potential:

1. Survey the market.

Surveys can be expensive, formal, affairs conducted by research companies using focus groups and statistical analysis. They can be as simple as asking for a few opinions from friends and members of your family. The Invention City Survey is a good tool for performing this research on your own.

There is an art to conducting surveys and even huge corporations make colossal mistakes. RJ Reynolds spent nearly $100 million developing a healthier, smokeless, cigarette called Premier. Upon introduction in 1988, Premier failed dismally. The people who tried Premier said it tasted, "like a fart." Others compared the taste to burned lettuce. Reynolds' surveys focused on the market potential for a healthier cigarette and failed to consider that, for cigarette smokers, health came second to taste and overall experience. The company assumed that the demand for health was high enough that even a bad tasting product like Premier would find success. The company was wrong.

Twenty five years later a new form of smoking with electronic cigarettes has emerged called vaping. Vaping is said to be much healthier than traditional smoking. But the reason for its success is that vapers can choose from a huge range of good tasting flavors and are not limited to tobacco.

Asking the right questions is the key to getting the right answers. Of all the questions an inventor should ask, the ultimate question comes back to simply this: will anyone buy my product? The best way to get an honest answer is to have actual samples of the product (working prototypes or pilot production) to show, demonstrate and possibly even sell. Unfortunately this conflicts with our goal of saving time and money. Therefore, at the beginning stage, a crude drawing, even an oral or written description can be used in surveys. If you cannot get a yes from someone, anyone, then it is time to invent something else.Once an inventor has determined that there seem to be customers for the invention, the question becomes whether or not the invention can be profitable, not just for the inventor, but for all of the parties involved in the commercialization process. Answering this question requires estimating a retail price at which the item will be successful and then finding out if the item can be made for a price (with acceptable quality) that allows you and your partners (retailers, marketers and manufacturers), to profit.

Often the true cost of manufacturing a product is not known until long after the product has been introduced. A complete and accurate estimate of costs requires a product to be completely engineered and designed. This is a time consuming and expensive process that should best be put off until after the inventor has committed to moving forward. At preliminary stages, cost estimates for making the product can come from looking at similar items that are already being sold.

Likewise, in addition to surveys, looking at retail prices for similar, alternative and competing items can provide clues for retail pricing. A rough guide for consumer products is that retail cost is four to five times manufacturing cost. If you can find products that utilize, more or less, the same components in a more or less similar structure, those products alone can provide a rough guide for your estimates. Alternatively, you might look at multiple items to find representations of the various aspects of the invention.

Let's say you invented a hybrid flashlight/screwdriver. You could go to your local mass merchant and look at the prices for flashlights and screwdrivers. Your item could not sell for less than either item alone since it would certainly cost more to make. At the same time the cost to make a combined product should be something less than the cost for making the two individual products. Some parts are shared. For example, the handle of the screwdriver could become the battery compartment for the flashlight; the costs for packaging and distribution are paid for only one item instead of two.

This brings us to the second step:

2. Estimate the retail price.

Now it is time to review the survey results or better yet, to survey again. Do people want to buy your product at the minimum retail price you've approximated? If people generally hesitate or say "no" to the estimated retail price, it is time to reconsider the project.

There are costs that need to be paid and money to be made as a product moves its way from drawing board to factory floor to warehouse to sales representatives to retailers and finally to customers. Each link in the supply chain costs money. Money for raw materials, labor, equipment, services, transportation, warehouse space, manufacturing space, office space, shelf space, packaging, advertising, customer service, telephones, inventor's royalty, legal and accounting fees, taxes, etc.

A typical rule of thumb for consumer products is that the manufacturing cost for an item is 20% of its retail cost at a conventional retail outlet such as Sears. It is likely that a product retailing for $20 costs no more than $4 to make. (As products become more expensive this ratio changes and the manufacturing proportion rises. Thus a video camera selling at Best Buy for $1000 might initially cost $500 to make - including amortization for tooling and R&D).

Just as the best way to survey the market is with a working, finished model, the best way to know the cost of manufacturing your invention is to actually have it fully engineered, designed and quoted upon. Once again, however, our goal is to make a determination before spending all that time and money.

This brings us to the third step.

3. Estimate the cost of manufacturing.

Use existing products as guides to infer costs from retail prices and other information. Saying that a product retailing for $20 should cost $4 to make does not mean that there are profits of $16. It means that there could be combined net profits of roughly $7.50 for both the manufacturer and the retailer. Net profit means profit after all the expenses have been paid, the money that's pocketed at the end of the day.

Here's a rough breakdown on where the money might go for a prototypical new product (from a new vendor) retailing for $20 at a mass merchant:

Manufacturer

Product: labor, materials, in-bound freight, tooling etc. | $ 4.00 |

Other Business Expenses: (engineering, marketing, salaries, rent, ROYALTY, etc.) | 3.50 |

Total Cost | 7.50 |

Wholesale Price | 10.00 |

Manufacturer's Net Profit | $2.50 |

Retailer

Product Cost | $10.00 |

Business Expenses (salaries, rent, marketing, etc...) | 5.00 |

Total Cost | 15.00 |

Retail Price | 20.00 |

Retailer's Net Profit | $ 5.00 |

To manufacturers and retailers the product itself is really unimportant. Manufacturers and retailers are in the business of building and selling boxes, boxes that contain profits. A new product is an opportunity to sell additional boxes that hold additional profits. No one really cares what's in the box! The value of an invention to a manufacturer or retailer is specifically the profits it represents. Features and benefits are merely mechanisms by which consumers are motivated to buy the box.

Once an invention has been reduced to a box it should be clear that manufacturers and retailers can easily substitute one box for another. No matter how special the invention in the box, no one will make it or sell it unless the box holds profits at least equal to or better than those of other, alternative boxes. In the case of real world retailers and catalogs (as opposed to internet retailers) shelf and page space are limited and products are literally chosen for their ability to pay "rent" on the retail space they are allocated. Products that fail to pay are evicted.

I knew an inventor who, upon hearing that Sears might sell his product for $20, said, "ok, I want them to pay me $17." Sears said that they would pay no more than $10 (they were planning to advertise the item with a big, expensive TV advertising campaign). The inventor responded with a price of $13 and Sears lost interest. Had the project moved forward Sears almost surely would have sold several million units and the inventor could have made several million dollars. Instead, the inventor went on to earn very little from his invention.

Everybody is happy to make money. Make people happy with healthy profits and they'll return the favor by helping you develop, manufacture and sell your invention.

This brings us to the fourth step:

4. Determine if everyone involved make better than normal profits.

Consider the difference between the estimated retail price and the estimated manufacturing cost.

The best reason for a manufacturer or retailer to make and sell your product is that your product makes them more money than other products. In considering this point, it is important to look at the total picture. If your product is easier to make, sell or service than other items, manufacturers and retailers might be happy with a lower profit percentage; likewise if your item sells in higher volume. For a given use of resources, the lower profit percentage could be more than compensated by higher profits overall - at the end of the day it's possible that more money may be made from your product (with regard to its use of shelf space, manufacturing equipment, people, etc.) than from others. But... but... but...

Even if it is true, inventors should be wary of using the argument of higher volume to justify lower than normal retailer and manufacturer profits. Manufacturers and retailers are unlikely to believe you; they feel that all inventors believe their inventions will sell millions upon millions. There is a tremendous credibility problem. Manufacturers and retailers probably won't believe that higher volume will happen until after it has happened.

Here is the bottom line: if the profits available from your product are perceived to be less than others, you will have an uphill battle.

While manufacturers and retailers care only that boxes contain profits, consumers care only that boxes contain useful features and benefits. Retailers marketed the Pet Rock because it earned high profits; consumers bought it because it had the benefits of being funny, new and different.

In our society there are alternatives for everything. For established market categories the many alternatives are often nearly exact substitutes; consider breakfast cereals, soaps, headache remedies, stereos and compact cars. For newer market categories the alternatives are older technologies. Cordless phones compete with cord phones; cell phones compete with pagers and pay phones. When first introduced, personal computers competed with typewriters. In some cases the alternative is to do without the technology altogether. Even though a private plane would significantly cut the travel time to visit my wife's family, we do not own and fly a plane. We drive a car. If a car were too expensive we'd travel by train or by bus.

The consumer always has the choice of buying an alternative product or buying nothing at all. Always!

If an innovation delivers benefits greater than its costs, users have reason to adopt the innovation. Each user views costs and benefits differently. This is the basis for the demand curve familiar to economics students. At lower and lower prices, more and more of a thing is sold. The thing could be first class airline seats, lobsters or toothpicks. With a few weird exceptions, the rule is that as the price of a thing goes down, more people will buy it. In considering the value of an innovation it is critical to think of the user and how and why the user will value it with respect to alternatives.

Imagine a brilliant new machine that turns lead into gold. It only works with a hand crank, cannot be automated and for metaphysical reasons must be located in North Dakota. If you put in one pound of lead and crank for 48 hours you get one ounce of gold. In this example the price of gold is fixed at $240 an ounce and the machine, the lead and the work space are available free of charge. Even with all of the free stuff, few people would want this amazing machine. Working the machine for 48 hours produces only $240 or $5 an hour! More money could be made by flipping burgers at a McDonald's in warm Miami for minimum wage. In this example, working at McDonald's is an alternative that is preferred to cranking out gold!

There is no doubt that a machine that turned lead into gold would be acclaimed as brilliant. The inventor would be featured on the cover of magazines and on innumerable TV talk shows. Nevertheless, if it took 48 hours of hand cranking to turn out one ounce of gold, few people would want the machine, even if it were free. The inventor would make no money. The machine would be a commercial failure.

If that same machine produced an ounce of gold with a mere 6 hours of cranking, the machine would have an output worth $40 an hour - so long as gold remained at $240 an ounce. Now the machine is probably worth buying. How much a buyer might pay depends on the cost of running the machine (including maintenance and supplies), aversion to freezing winters in Bismarck and the risk that the price of gold might go down in the future - if lots and lots of people start making gold, then gold would cease to be scarce and the price of gold would plummet. Furthermore, the lead and workspace that are free today in this example could become quite expensive tomorrow.

In valuing a new product, a customer therefore considers both the potential benefits and the costs and risks associated with receiving those benefits. I do not mind spending $15,000 or more on a car if I believe it will run over 100,000 miles trouble free. If I expect the car to need service after 5,000 miles the value of the car goes down considerably. This is why Toyotas sell for more than Yugos. This does not necessarily mean that I would buy the Toyota. At one set of prices I will choose the Toyota. At another set of prices I will choose the Yugo. Cheap enough, the Yugo becomes a better value than the Toyota. Too expensive, the benefits of the Toyota are lost.

Toyotas and Yugos deliver the same primary benefit of transportation. One can be easily substituted for the other to get from here to there and back again (even if the Yugo requires a repair stop for the return journey). If time were irrelevant and the cost of a car (taxi, train, bus etc.) high enough, walking would be an alternative too.

In considering alternatives it is also important to look ahead and consider what will be coming soon. In 1995 it was clear that the internet could perform many of the same functions as a fax machine. An inventor of an improved fax machine in 1995 would therefore have been wise to consider the internet as an alternative to his invention.

Here then, is the fifth step:

5. Consider present and future alternatives.

No matter how good your invention is, a customer can always choose something else. Just because a customer does not know the alternative today does not mean he or she won't know it tomorrow. When performing surveys respondents should be informed about alternatives to discover how the invention fares in a competitive environment.

Manufacturing and commercializing a product requires investments that are typically amortized over some or all of the anticipated life cycle of the product. When Boeing sets a price for a new plane, the price includes a portion of the plane's billion dollar cost for development. To keep the price of the plane competitive, Boeing may forecast receiving that portion for each plane sold for a period of ten years or more. Therefore Boeing must forecast the life cycle for the plane before it begins investing in development. Boeing needs to believe that the plane's life cycle will be long enough to recover development expenses (while remaining competitively priced) otherwise Boeing will drop the project.

Inventors of products like the Pet Rock must make similar calculations. The amounts involved are likely to be much smaller. For example, something like the Pet Rock could probably be brought to market for less than $20,000. It's possible that $20,000 could be recovered with the first order. In this case, since amortization is more or less instantaneous, life cycle is irrelevant.

Obviously, the longer the life cycle the more money an invention earns. A longer life cycle reduces the risk of investing in the project.

In general, the biggest threats to a product's life are new technologies and responses from competitors (in the case of fad items like Pet Rock it is the fact of being a fad). To a degree these things can be forecast. Thus the next step in evaluating an invention is:

6. Estimate the product's life cycle.

Determine if the life cycle is long enough to both recover investment in development and earn a healthy return on effort and risk.

Finally we have reached the point where patents may be relevant. A patent is the right to exclude others from using a specified technology. This can impact the potential responses from competitors and enable higher than normal profits. However, a patent can take several years to issue and enforcement of a patent is not possible until after the patent has issued. Pending patents can not be enforced!

An inventor may therefore think it wise to wait until a patent has issued before commercializing an invention - unfortunately this means that the invention will probably enter the market two or three years later than if the inventor had not waited for a patent to issue. During that time competitive products may have entered the market, possibly including competitive products that directly violate the pending patent! In a worst case scenario an inventor could see a patent issue just as the life cycle for the invention is ending. In general, therefore, being first to market matters far more than having an issued patent.

One further point about patents should also be understood. Issued patents can be challenged and revoked. A competitor illegally utilizing technology claimed in a given patent may claim, upon being sued for patent violation, that the given patent is not valid; the competitor may point to prior art patents in the public domain or to some product offered for sale in Outer Mongolia ten years prior to the patent filing date.

I raise these points to knock some glitter off the patent god that all inventors worship. Nonetheless, patents can be incredibly valuable assets. In fact, most large corporations will not license an invention unless it has the potential for meaningful patent protection. The issue here is what value does the patent add to the invention?

A patent gives the holder the exclusive right to make use and sell a specific implementation of a technology for a period of time. In the United States that period is now twenty years. If the technology protected by the patent is necessary to your invention, and your invention is successful, and your invention has a life cycle of more than a few years, this exclusive right can be quite valuable. An issued patent can help in preventing competitors from copying your specific implementation. An issued patent will NOT prevent someone from copying your idea unless the only way to execute the idea is by using the specific implementation claimed (or found to be equivalent to a claim) in your issued patent (and the patent is held valid in any subsequent legal disputes).

A patent's value depends directly on one factor: Its ability to create higher profits. Increased profits can come by enabling lower costs (costs of production, safety, environment etc.) or through features and benefits that buyers will pay a premium for. If a patent does not enable higher profits then it is, theoretically, worthless.

As part of the profit consideration the costs of patent enforcement, filing and maintenance should also be considered. What are the chances that another inventor will sue claiming rights to the patent? What are the odds that someone will successfully challenge the patent? What are the costs for filing and maintaining all of the relevant patents in the US and worldwide?

The more successful, the more visible a product is, the more likely that there will be challenges to the patent in one form or another. The cost for filing a relatively simple US patent for a mechanical device is approximately $10,000. Having that patent filed and issued in developed countries worldwide could add another $50,000 - $100,000. Patents can rarely be combined; more often they are broken up into multiple patents. Therefore, the inventor must consider the costs for each patent.

When all of this has been considered the inventor can then a) estimate the total unit sales of the invention over its life cycle; b) multiply the total unit sales by the estimated additional profits a patent will enable; and c) subtract the estimated costs for obtaining and maintaining the patent(s). Now it's time to take the final step in evaluating the invention:

7. Estimate the value of patent(s).

You may discover that patent protection is not worthwhile. You might also determine that Sony should gladly pay you $10,000,000 for exclusive rights. Keep in mind that, however you perform your calculation, there is a virtual certainty that third parties will view your estimates as optimistic. Also know that, if licensing is a goal, most large firms have rules about royalty rates. Each industry has its own rules. In the hand tool industry, for instance, royalty rates of 2-4% are common and rates above 5% are pretty much unheard of.

In addition to making licensing an attractive option, a highly valued patent can be extremely helpful in raising funds to launch a new venture. A strong patent reduces the risk of moving ahead by securing a competitive advantage.

Here is a summary of the steps:

1. Survey the market.

2. Estimate the retail price.

3. Estimate the cost of manufacturing.

4. Determine if everyone involved can make better than normal profits.

5. Consider present and future alternatives.

6. Estimate the product's life cycle.

7. Estimate the value of patent(s).

Now you should have a good idea on whether or not the invention is worth serious time and effort. Good luck!

Mike Marks is President of Invention City and has been active in the field of product development since 1987.

share this article: facebook

Inventor

I have a product that I believe in just as a womans point of view. I have sold some of my product and people i tell that they will be in stores soon. I just have had so many marketing people call me that I dont know which way to go. Money to Market my product that I have invented and produced. This is a product that I know can be sold and made money with. I have had 40,000 made in Turkey and very proud of my product. I would love to be able to make money off of my invention and also have a product that I invented that was a success. This is my story. Always suggestions are welcome to me now. I say I cant figure it out and God says he will direct me..

by: Connie Voga